I interviewed agricultural researcher Tom Geiger via chat. We talked about the technological struggles of sustainable farming and the grim future-present. This Q&A is heavily edited to be more readable, but Geiger had a chance to review the edits and make sure his meaning was preserved. He works at a university on a Caribbean island.

Okra photographed by Rebecca Wilson.

Tom Geiger: My current project has two parts: vegetable variety trial and irrigation equipment evaluation. The variety trial part is comparing three different okra varieties to see which one is the best for our local conditions. The okra is being irrigated with four different kinds of plastic drip irrigation lines, with emitters spaced every foot. We are comparing pressure-compensating and non-pressure-compensating drip lines. [There is an expanded explanation available if you’re interested.]

We have no rivers or streams on the island. All fresh water comes from wells, harvested rainwater, or desalination. Water conservation is especially important here and in island communities in general. One goal of this project is to encourage local farmers to increase their irrigation efficiency by switching to pressure-compensating drip tapes.

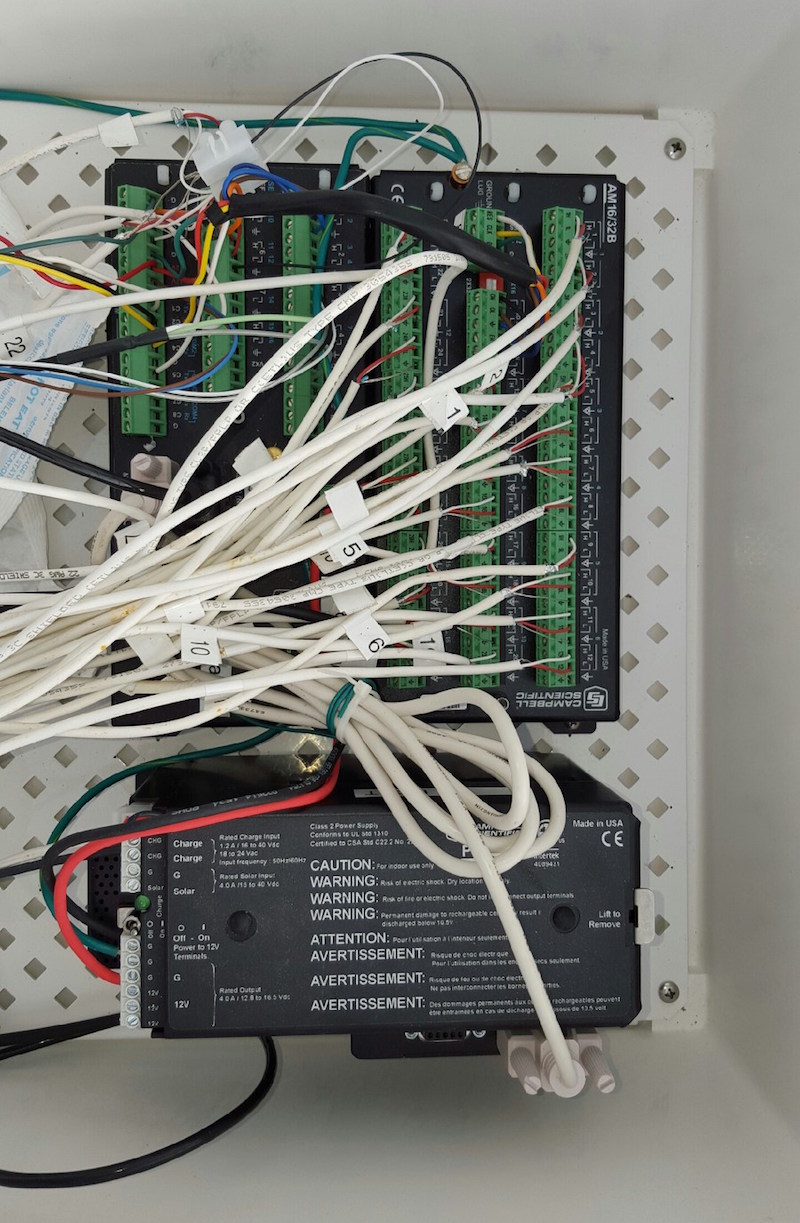

This current project isn’t automated, but I am working on another project using sensors to control irrigation in hydroponic cucumbers. Sensor-based irrigation is increasingly popular, especially with larger farms and greenhouses.

Photo courtesy of Tom Geiger.

Exolymph: So how did you get into doing this work personally? Is it what you studied?

Tom Geiger: I started out as an engineering student but it wasn’t as fulfilling as I thought it would be. During my sophomore year I attended a lecture on world food issues, which really opened my eyes to the problems and possibilities of agriculture. I switched my major to horticulture and started working as a researcher here in the Caribbean after graduation. I had planned on working for commercial growers but research has been a nice experience.

Exolymph: Do you find that most of your colleagues have similar motivations?

Tom Geiger: I think people get into agriculture for a lot of different reasons, but yeah, there are many people who choose this field for idealistic or ideological reasons. Who doesn’t want to save the world? Agriculture can be improved at local, regional, and global levels. You have people with all sorts of different perspectives and all of them are important.

Exolymph: Do the commercials farmers you talk to feel similarly?

Tom Geiger: Yes, it’s common. Or at least people here feel like they are doing a good thing for the island. Local agriculture definitely makes sense on an island. People need to eat every day. It’s easy to feel good about contributing to that.

Exolymph: Does academic agriculture have its own culture separate from production agriculture or do they intermingle a lot?

Tom Geiger: Well, it is academia. We go to conferences and publish in journals. But I don’t think ag researchers are as much in the ivory tower as other academic types. I know a lot of commercial farmers personally. Small farms because it’s an island. We work with the farmers, and you’ll find that a lot of universities have agriculture extension services.

Exolymph: What are some good first steps for people looking to incorporate higher tech into their gardening? Does it make sense for laypeople to do that at all?

Tom Geiger: Knowing when and how much to irrigate is the hardest part besides pest control. Scalable, automated irrigation systems could make gardening accessible to more people, whether they have a plot of land or only a potted tomato plant on the patio. Decentralization is cool, but I’m not against large farms.

I would like to see more gardens and less lawns. That would be a great way to decentralize and localize production in places where people have a yard. The hard part is for people to find the time to take care of their gardens. I’d like to see some kind of decentralized gardening service, like Uber for gardens, that would connect people who have small plots of land with people who have the skills to grow produce.

Exolymph: Are some people opposed to large farms no matter what?

Tom Geiger: I’d say that small and local is popular right now, but it needs to be done right. Imagine ten small farms with ten tractors, ten small walk-in coolers to store the produce, ten minivans to transport it to the co-op… Versus one farm ten times as big which only needs one of each of those things.

It’s hard to wrap your head around everything that goes into running a vegetable farm. There’s a lot to consider, like economies of scale and the carbon footprints of the farm, transportation, and storage. We need more research to find a balance between efficiency and sustainability.

Even defining local food is hard. What is local? Ten miles, fifty, 100? Half the global population lives in cities. It might be possible for a city like Los Angeles to source all of its food locally by some definition but probably not efficiently or sustainably.

Exolymph: Why do you think people prefer small farms?

Tom Geiger: It’s mostly political. Wendell Berry and all that. People want food sovereignty. They want to know where their food comes from, to feel a connection to it, to strengthen the community and keep food dollars in the local economy. They want to support small farmers who they know and can relate to, rather than faceless corporations which often seem more interested in the wellbeing of their shareholders than the people and the environment. All of those are good and noble reasons to support local food.

Exolymph: Do you think people who don’t work closely with agriculture have a realistic view of “how things ought to be”?

Tom Geiger: I totally agree that small and local is ideal sometime in the future, especially once we have more data on what you get at different levels of small and local. We have seven billion people on the planet — like I said, half of them live in cities.

When it comes to feeding the urban population it’s hard to define “small” and “local” in a way that’s still meaningful. “Large” and “distant” agriculture is the reality for many people and it will be that way for a long time despite our best efforts. I think the kind of people who demand everything small and local don’t really understand how big of a challenge it is.

Photo courtesy of Tom Geiger.

Exolymph: How does technology play into this? Is the use of the type of irrigation gadgets that you’re researching well understood but needs to be adjusted for specific microclimates, or is it greenfield? (Excuse the pun.)

Tom Geiger: Like William Gibson said about the future not being evenly distributed, the technology is here — it just needs to be used. For example, you can irrigate based on evapotranspiration data from weather stations or satellites, but not everyone is using it so they are likely over- or under-irrigating. The moisture sensors are better for greenhouse crops. I don’t see any reason not to use evapotranspiration for field crops, and it has been researched since the 1960s. Add in self-driving tractors, drones, and automated harvesting. But then what do all those people do that are replaced?

Exolymph: Oof, yeah. Technological unemployment has already hit agriculture really hard. Do you have any prospective answers?

Tom Geiger: I have no idea. Basic income. And then what?

Exolymph: You mentioned earlier, “One goal of this project is to encourage local farmers to increase their irrigation efficiency by switching to pressure-compensating drip tapes.” How is that goal progressing? What’s the reason for farmers not to switch — just inertia, or the up-front expense, or…?

Tom Geiger: Mostly inertia. Using your old drip tapes until they’re full of holes, not knowing what is available, not having good options because there are no local distributors, being broke. Agriculture is seriously underappreciated. I know many farmers that are just getting by. But we have to keep food prices low, because if people can’t afford to eat they will demand higher wages.

Fixing things is a tough question because even the answers people usually give like “buy local” are not silver bullets. Know your farmer, buy local, and buy fair trade if you can, but don’t get all elitist on the people who don’t or can’t. I mean, it’s great if your food comes from farms that do XYZ and maybe that’s the ideal situation, but we can’t fix agriculture overnight.

Exolymph: It’s rough. Especially when you look at proteins as well as produce — ethically raised meat is sooo expensive.

Tom Geiger: Yes, and in fact manure is extremely useful for sustainably managing soil nutrition. To get high yields you are using either synthetic fertilizers or animal byproducts. Some people who are against synthetic fertilizers are also against raising livestock but it’s really hard to have it both ways. I used to work on an organic farm that used fish emulsion, bat guano, and composted turkey litter. A lot of people don’t realize the importance of livestock on organic vegetable farms.

Exolymph: What do you think of the various ~omg future of food~ initiatives like Soylent and cricket flour and such?

Tom Geiger: They have their place, but it’s unlikely that we’ll see those things as a staple. If people stop reproducing so much we won’t have to worry about a future like that, but that’s not really my area of expertise.

Exolymph: “If people stop reproducing” is my wheelhouse in terms of ethical commitments, but I have no idea how to make people do that.

Tom Geiger: Right?