I’m still thinking about how to structure the rewards for readers who financially support Exolymph. But one of the current ones is that people who contribute $10 via Patreon can choose a topic for me to write about. Beau Gunderson posed the question, “What would a cyberpunk social safety net look like?”

A social safety net is a formalized way of catching people when they fall. Traditionally, the government pays for a few survival-level services, like food stamps and homeless shelters in the United States, or healthcare in more civilized countries. (Sure do love our privatized medical system that totally doesn’t punish the poor!)

But a cyberpunk future-present is dominated by corporations rather than the state — would they be inclined to pick up the slack?

In a way, the ideal version of a cyberpunk social safety net would be a bit like how things used to function for the middle class. You had a decades-long career at a big company; in exchange for your labor and loyalty, they provided your family’s healthcare and a pension. The Baby Boomers are the last generation to participate in this scheme.

I don’t mean to romanticize the past — a lot of things about the 1950s through ’90s were awful, especially if you were a person of color, a woman, LGBTQIA, or any combination of the above. Even if you were a straight white man, striking out on your own, whether as an entrepreneur or a societal dropout, was pretty risky. (It’s still pretty risky.)

Regardless, the “work for BigCorp until you turn sixty-five and eat cake at your going-away party” paradigm is being dismantled by the twenty-first century. “Precariat” is a hot buzzword; labor is contingent and people hop from gig to gig.

Workers get shafted unless they have particular scarce skills (like programming or deceiving the public). Broadly speaking, the causes are globalization and technological advances. No need to pay for benefits in [rich country] when workers in [poor country] don’t expect them!

At this point I’m just reviewing things you already know.

One vision of ultra-capitalist social services comes from radical libertarian David Friedman (as quoted by Slate Star Codex):

[A]t some future time there are no government police, but instead private protection agencies. These agencies sell the service of protecting their clients against crime. Perhaps they also guarantee performance by insuring their clients against losses resulting from criminal acts.

How might such protection agencies protect? That would be an economic decision, depending on the costs and effectiveness of different alternatives. On the one extreme, they might limit themselves to passive defenses, installing elaborate locks and alarms. Or they might take no preventive action at all, but make great efforts to hunt down criminals guilty of crimes against their clients. They might maintain foot patrols or squad cars, like our present government police, or they might rely on electronic substitutes. In any case, they would be selling a service to their customers and would have a strong incentive to provide as high a quality of service as possible, at the lowest possible cost. It is reasonable to suppose that the quality of service would be higher and the cost lower than with the present governmental system.

If you want a LOT more speculative detail about edge cases and such, read the SSC review (or Friedman’s book itself). To be clear, I don’t think privatized protection agencies are a good idea.

The cyberpunk social safety net that would be easiest to implement is a sort of collectivized insurance, modeled on Latinx tandas — lending circles. You could probably even incorporate a blockchain to make it trendy — or possibly to make it scale better? I am not a software engineer. Anyway, imagine this:

Every month, fifteen friends put money into a pot, which is kept by a mutually trusted member or a trusted third party (e.g. church pastor or bank safe). Whenever one of the friends has a crisis, like losing their job and needing to cover rent, the necessary funds are dispensed to them.

Before you email me, yes, there are a million ways this would be complex and difficult in practice. What if someone tries to claim something that a third of the group thinks is a illegitimate expense? Okay, majority rules. What about vote brigading? How do you vet people who want to join?

Mixing social relationships and money tends to be tricky.

That doesn’t even address the problem that arises when someone undergoes a real catastrophe and needs hundreds of thousands of dollars to start resolving their issue. But hey, it might be better than nothing. It might help the half of the American population who can’t come up with $400 in an emergency.

If that’s not pessimistic enough for you… I asked members of the chat group to weigh in, and @aboniks elaborated at length:

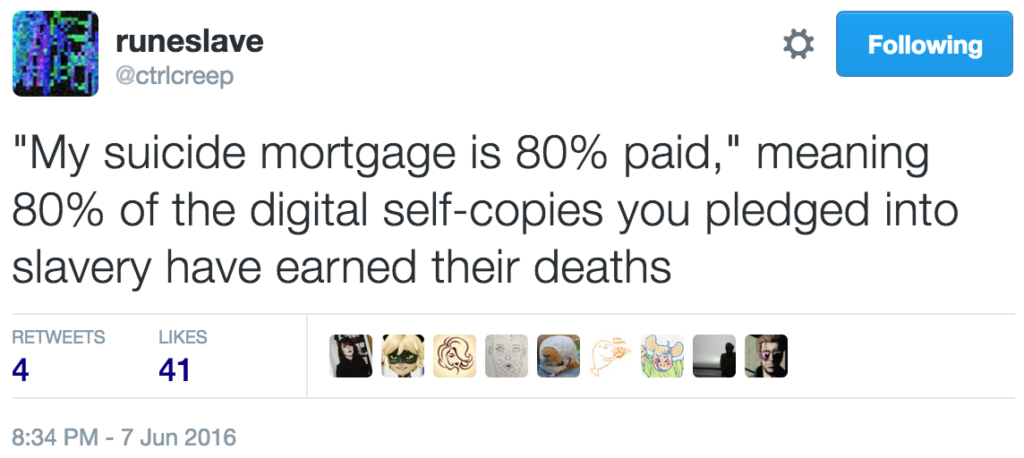

If this is a cyberpunk vision where people can be digitized, social security is basically a programming exercise, right? The safety net is actually a safety network. Contractors design theme parks for our digitized psyches and call it a day. Or people each get X amount of storage space and X number of processing cycles to run their own virtual retirement. AIs sell them experience-design services. People duplicate themselves with falsified credentials to engage in benefit fraud and increase their storage space.

Political arguments over meatspace benefit levels and healthcare could translate into arguments about involuntarily putting people into hibernation mode. Article 12 of the Digital Rights Act ensures equal access to services, but people with certain neurological conditions are being discriminated against when they apply for control of real-world mobile camera platforms; rich meatspace Thiels find the erratic movement of their drones to be unsightly.

Anyway, however you pitch it in the end, keep in mind that social security is fundamentally about having and not having. It’s going to be the believability of the conflict between the service users and the service providers that makes your vision work. Or not work.

More realistically, I expect we’ll see something like the private prison industry being broken up and reforming as a service provider for social security beneficiaries. The idea that we’re all going to have a 1/1 bungalow with a garden and an aging Labrador in front of a crackling fire… no. Looking at how people with only SS income are living these days, even an institutional housing project with razor-thin profit margins would be a quality-of-life improvement for a lot of urbanites. The extended family is largely a thing of the past unless you go out of your way to make it happen, and the nuclear family is headed the same way. Lots of poverty-line “senior singles” in our future.

I’m still looking into incorporating my family though. The future I’m likely to live through is much more friendly to corporations than it is to humans.

(Lightly edited for style consistency.)

So, what do you think?

Easily the best response, from reader Brett:

Maybe in a cyberpunk social safety net, there would be a (computer) program that would calculate and dictate when volunteers should steal a roll of toilet paper from their work. The toilet paper would be hoarded and then sent along to those who need it. The computer program would subtly manage the rate of stealing across its networks of humans so the thievery is distributed across many different corporations and never detected by competing algorithms looking for “leakage” in their expenses.