“Neural Fintech” got more responses than anything else I’ve ever asked you all about, so it’s back *TV infomercial voice* by popular demand! If you missed the beginning you don’t strictly need to read it, but you can if you want to.

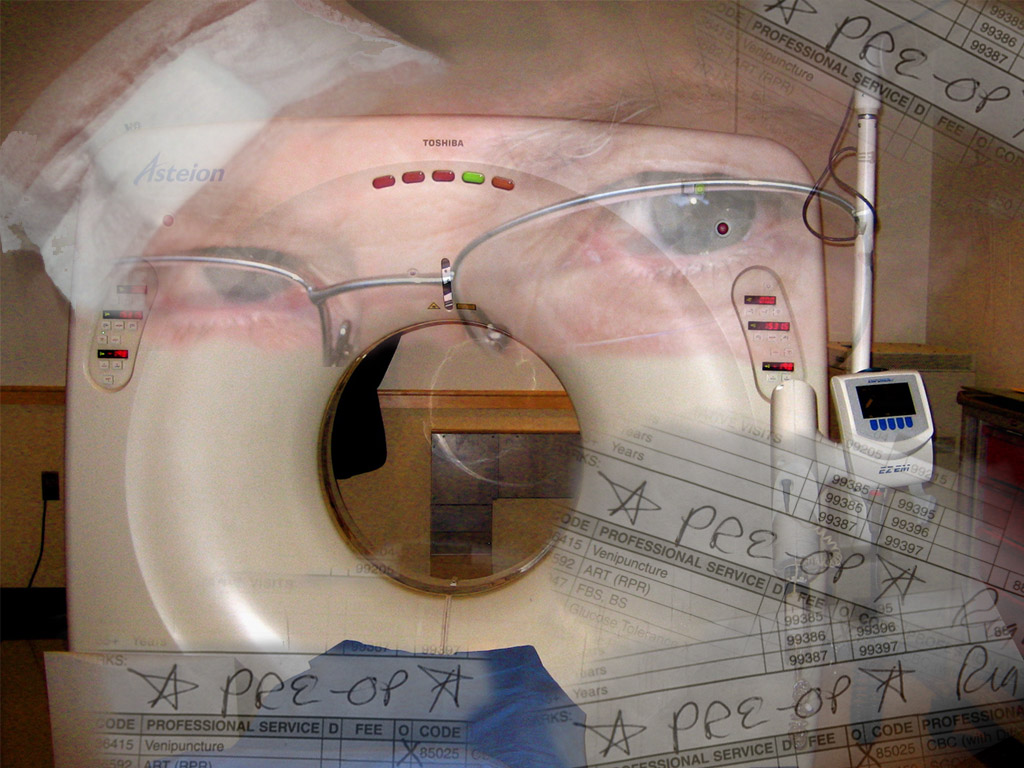

In the examination room there was machine that looked like an old-school MRI unit — Sasha remembered them from the hospital shows her grandma used to watch, 2D video of handsome doctors clumsily enhanced for her parents’ RoomView.

Next to the machine stood a beaming nurse with sleek brown hair. Everyone working for Centripath seemed to smile all the time, Sasha thought.

Jake the recruiter exclaimed, “Becky! Help me welcome our newest participant!”

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, Sasha,” the nurse said in a warm voice. On the machine’s side screen, Sasha could see the permission form that she had signed with Jake a few minutes ago.

“You’re in Becky’s hands from here,” Jake said, winking at Sasha as he slipped back out through the door.

The next few hours were busy and regimented. Multiple tests, the first inside that big machine, and then more forms. Sasha was glad that she hadn’t made plans for the rest of the day, but a little annoyed that no one had told her how long it would take.

She found out from Becky that she had “stellar capacity” for a crypto mine. Sasha tried to ask again how much they would pay, but Becky said she’d have to find out from her case manager. “That’s your next stop!” she told Sasha brightly. “Then installation!”

The case manager’s office was like Jake’s, and he even looked a bit like Jake. The nose and chin were different, but much the same smile. “Sasha, right?” he asked, half-rising from his desk.

“Hi,” she answered. Sasha could hear that she was tired.

“Would you like a drink of water?”

“Yes, thanks.” He handed it to her, and Sasha sat down.

“I really want to know how much this will pay. No one will tell me so far.”

“Of course, of course! You get a percentage of the yield from the mine. It can vary depending on your physical state, since all the energy is sourced from your body.”

Sasha didn’t say anything, just kept looking at him.

The case manager paused, waiting for her to acknowledge what he said. When she stayed silent, he continued. “It’s usually 5%, but that fluctuates based on the price of the cryptocurrency at hand, the daily processing efficiency, and so on.”

“Please estimate, in real money, how much I can earn from this.”

“Well, Sasha, I can’t promise anything. I can’t make a guarantee. But I can tell you that you’ll be able to pay half of the monthly fees for a nice PodNiche.”

She sighed. “Okay. I hoped it would be more. But okay, what the fuck. Let’s do the installation.”

Header image by Liz West.