I talked on the phone with Darius Kazemi, best-known member of the #botALLY community and whimsical internet artist. First things first — is it pronounced Dah-rius or Day-rius? The latter, he said.

This is how reality is created, by asking questions and assimilating the answers. We participate in making meaning with each other. It’s unavoidable — you can’t opt out of being a cultural force without opting out altogether; relinquishing existence. You can, however, pursue the opposite aim. Amplify yourself.

All this from name pronunciation? Am I getting carried away?

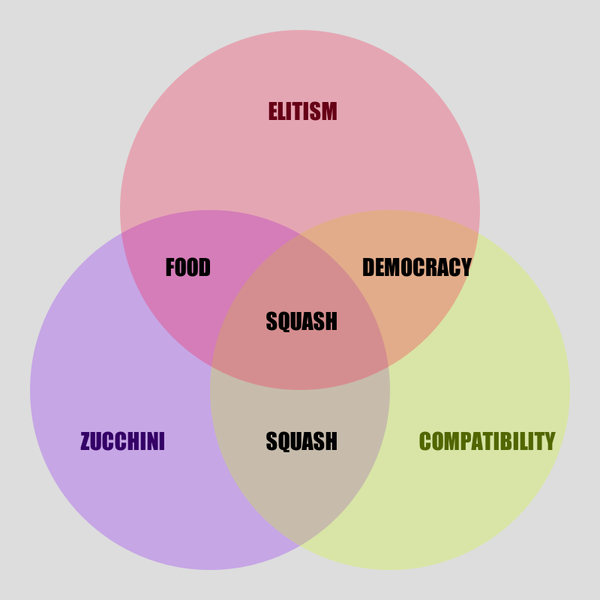

The latest nonsensical Venn diagram by @AutoCharts, one of Darius’ projects.

Darius used to make a living as a programmer. For years he worked in video games: “A lot of the core skills I learned making video games, I still apply to the stuff that I make today.” He wrote code to generate terrain, maps, and whole worlds. Now his creative practice is also his day job. Darius co-founded the technology collective Feel Train with Courtney Stanton. You can commission web art from Feel Train — for instance, they just finished developing a Twitter bot that will be part of a marketing campaign this spring. Of course, the members of Feel Train also continue express their own aesthetic urges.

I asked Darius to identify his cultural antecedents. He cited a variety of sources: Dada, the Situationists of the 1960s, William Burroughs’ cut-up poetry, and John Cage. “Name off your standard list of avant-garde early-mid-twentieth-century artists,” he joked. Then Darius mentioned Roman Verostko, who has been making digital art for almost fifty years. Verostko wrote “THE ALGORISTS”, an essay that functions as both manifesto and history. He describes algorists — those who work with algorithms — as “artists who undertook to write instructions for executing our art”, usually via computer. Verostko states, “Clearly programming and mathematics do not create art. Programming is a tool that serves the vision and passion of the artist who creates the procedure.”

Beau Gunderson told me something similar: “as creators of algorithms we need to think about them as human creations and be aware that human assumptions are baked in”. I’ve seen many algorists stress this principle, that computers can’t truly create. Programs only encompass process, not genesis.

Darius told me about a book that profoundly affected him: Alien Phenomenology by Ian Bogost. Here Darius was introduced to the possibility of “building objects that do philosophical work instead of writing philosophy”, as he put it. The concepts in Alien Phenomenology acted as “permission to do something that doesn’t even have a name”. Soon Darius began spinning up the bots that comprise his current “stable”, starting with Metaphor-a-Minute.

Philosophical underpinnings aside, Darius doesn’t regard his art as a heavy-handed intellectual exercise. His bots are conceived like this: “I think, ‘Blah is funny.’” Then he considers blah further and concludes, “I could make that. I should make that!” He says that bot-making is “way different from a game, where you have to beg and convince people to engage with it”. The bots invite interaction and duly receive it.

I asked Darius about power. He said, “I think a lot about the rhetorical affordances of bots, and how bots allow you to say things that you wouldn’t otherwise.” A bot allows its creator to express messages indirectly, through a third party. Darius continued, “Bots can get away with saying things that normal people can’t. […] People are very forgiving of bots.” We treat them like children or pets. He added, “Bots say the darnedest things!”