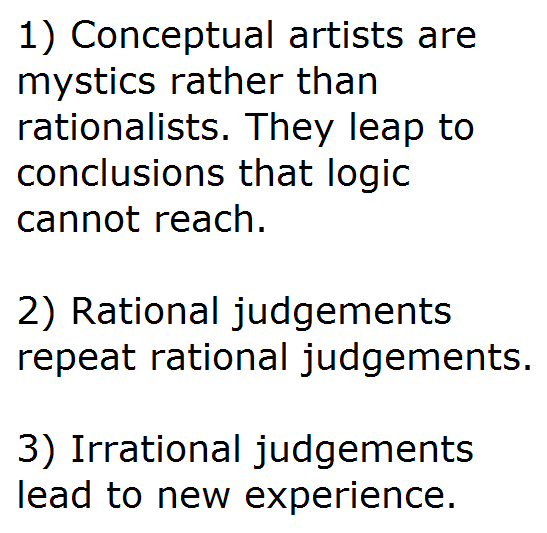

“If you’re doing something that nobody else is doing, it’s either really stupid or really smart. If it’s really stupid at least people will talk about it, but if it’s really smart you’ll have no competition.” Zach Gage on his creative process. He cited Lewitt’s “Sentences” as an influence.

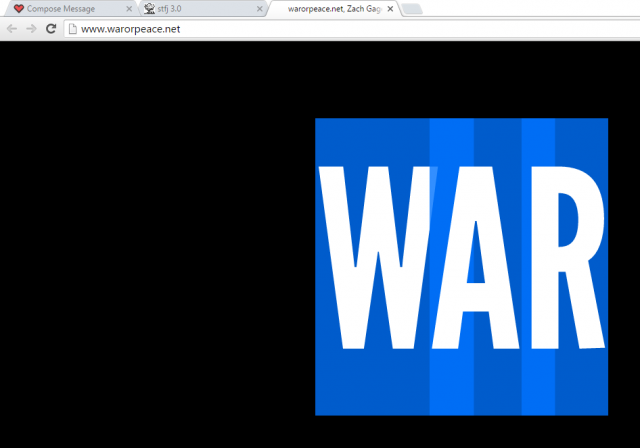

So who is this guy, anyway? Zach Gage is a conceptual artist. His work encompasses “games, sculptures, websites, talks, prints, photos, videos, toys, hacks, fonts, installations, and more.” He is best-known for iOS apps like Ridiculous Fishing and SynthPond. I’m struggling to summarize Zach’s work in a way that encapsulates why I find it exciting. Maybe an example will help — my favorite of his creations is warorpeace.net:

The site can display either “WAR” or “PEACE”, depending on how many people Google each word in a given day. The most-searched of the two words will win. Zach explained, “On the day that more people search for peace than war, the site will say peace. As of this writing, that has never happened, but the work awaits the day it does.”

warorpeace.net is more of a pure conceptual piece, but Zach’s bread-and-butter is game design. That’s how he makes most of his money, and based on his list of complete works, interactive creations are an enduring interest. I think it’s important to talk about the paradigms and techniques employed by game designers, because they have power. As virtual reality continues to gain traction, we’ll spend larger portions of time in worlds programmed by other humans. (Not necessarily a bad thing!)

On Friday morning, Zach and I talked about designing generative systems that manage to keep surprising people — including the creators. (We agreed that Olivia Taters does a great job.) I asked why systems intrigue him, and Zach said, “I think one of the biggest things is that people just don’t understand systems. It’s kind of a complexity thing.” Therefore system design “provides kind of a good target for art and a good target for games.”

Like many artists, he wants to make people think. Most of the time, we default to a sophisticated kind of autopilot. Zach told me, “You start doing things by pattern recognition and you do a lot less sitting, thinking, and wondering.” It’s a natural reaction, because we all have to get on with our daily lives — but it’s also valuable to be snapped out of the monotony. Zach likes to observe the rules of systems that people are following by rote, and try upending one assumption. This is a way to interrogate how things work — to prompt people to question their own habits and processes.

“There are not a lot of ways you can build something that will ask people to think,” Zach said. When people puzzle through a game and solve problems, they stretch their neural muscles and often feel good about themselves, especially if the story was also beautifully immersive. However, providing this experience is extremely difficult. Zach told me, “Designing games is really hard. It’s really challenging. You’re trying to design something that you yourself could never fully understand, because that’s what’s fun about games.”

When Minecraft became a huge hit, a lot of people released copycat games. Zach contends that they imitated Minecraft aesthetically without reproducing the core magic. He explained to me, “When you deal with randomness, most of what you get is just a regression to the mean.” For example, “The longer you generate [procedural] landscapes, the more you realize that although technically every landscape is unique, they’re all the same.” Ho hum, another winding river and a few more snow-capped mountains. Even if the contours are a little different, the way we perceive the environments and interact with them is the same.

Zach thinks that Minecraft “did a really good job tying together the generative components with these actual functional components” in a way that allowed people to apply meanings that resonated with them. (I wish I had asked him to elaborate on how Minecraft does this better than others.) In his own work, Zach tries to build depth and profundity into systems that use random elements. Zach wants to “make sure that [players] are engaging in the way that the stuff is the most interesting.” This is a tricky design problem, but he seems to be tackling it well.