A system is an arrangement of interlocking elements or moving parts that all affect each other, sometimes recursively. The world is full of them (and in fact each of those systems is itself an element of the larger system that comprises the whole universe).

Mathias Lafeldt wrote about how the human mind copes with this:

“Systems are invisible to our eyes. We try to understand them indirectly through mental models and then perform actions based on these models. […] Our built-in pattern detector is able to simplify complexity into manageable decision rules.”

Lafeldt’s explanation reminds me of the saying that the map is not the territory. Reality (which is a system) is the territory. Our mental models are maps that help us navigate that territory.

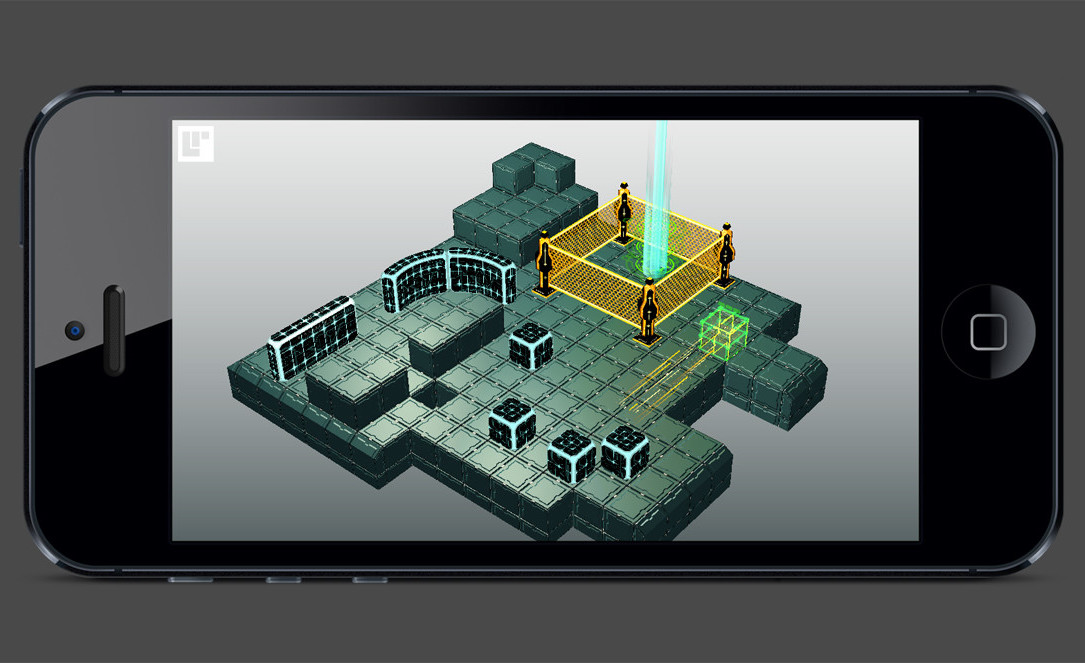

Artwork by Kyung-Min Chung.

But no map is a 1:1 representation of reality — that would be a duplicate, or a simulation. Rather, our maps give us heuristics for interpreting the lay of the land, so to speak, and rules for how to react to what we encounter. Maps are produced by fallible humans, so they contain inaccuracies. Often they don’t handle edge cases well (or at all).

Nevertheless, I like mental models. They cut through all the epistemological bullshit. Instead of optimizing a mental model to be true, you optimize it to be useful. An effective mental model is one that helps you be, well, more effective.

This is why Occam’s Razor is so popular despite being incorrect much of the time. Some plans do go off without a hitch. But expecting the chaotic worst is a socioeconomically adaptive behavior, so we keep the idea around. [Edit: Hilariously, I mixed up Occam’s Razor and Murphy’s Law — thereby demonstrating Murphy’s Law.]

My personal favorite mental model is a simple one: “There are always tradeoffs.” One of the tradeoffs of using mental models at all is that you sacrifice understanding the full complexity of a situation. Mental models, like maps, hide the genuine texture of the ground. In return they give you efficiency.