Mathias Lafeldt writes about complex technical systems. For example, on finding root causes when something goes wrong:

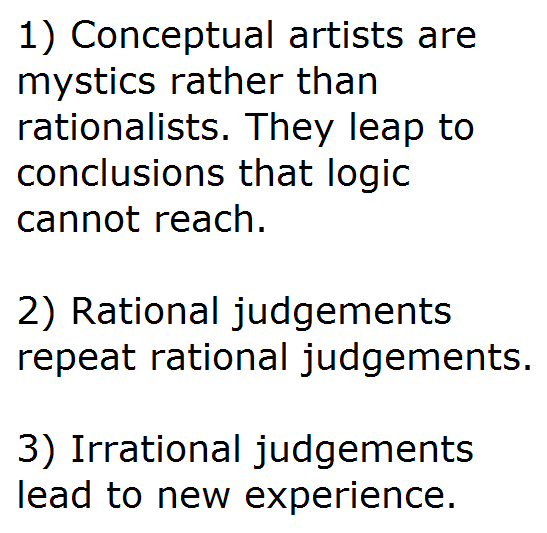

One reason we tend to look for a single, simple cause of an outcome is because the failure is too complex to keep it in our head. Thus we oversimplify without really understanding the failure’s nature and then blame particular, local forces or events for outcomes.

I think this is a fractal insight. It applies to software, it applies to individual human decisions, and it applies to collective human decisions. We look for neat stories. We want to pinpoint one factor that explains everything. But the world doesn’t work that way. Almost nothing works that way.

In another essay, Lafeldt wrote, “Our built-in pattern detector is able to simplify complexity into manageable decision rules.” Navigating life without heuristics is too hard, so we adapted. But using heuristics — or really any kind of abstraction — means losing some of the details. Or a lot of the details, depending on how far you abstract.

That said, here’s Alice Maz with an incisive explanation of why everything is imploding:

Automation is transforming bell curve to power law, hollowing out the middle class as only a minority can leverage their labor to an extreme degree. Cosmopolitan egalitarianism for the productive elite, nationalism and demagoguery for the masses. For what it’s worth, I consider this a Bad Outcome, but it is one of the least bad ones I have been able to come up with that is mid-term realistic.

Which corporation will be the first to issue passports?

Rushkoff argued that programming was the new literacy, and he was right, but the specifics of his argument get lost in the retelling. The way he saw it, this was the start of the third epoch, the preceding two ushered in by 1) the invention of writing, 2) the printing press.

Writing broke communal oral tradition and replaced it with record-keeping and authoritative narration by the literate minority to the masses. Only the few could produce texts, and the many depended on them to recite and interpret. This the frame (pre-V2 maybe) that Catholicism inhabits.

The printing press led to mass literacy. This is the frame of Protestantism: the idea is for each man to read and interpret for himself. But after a brief spate of widely-accessible press (remember Paine’s Common Sense? very dangerous!) access tightened up. Hence mass media as gatekeeper, arbiter of consensus reality.

The few report, and the many receive. Not that journalists were ever the elite, just as the Egyptian scribes. They were the priestly class, Weber’s “new middle”. (Also lawyers. Remember the backwoods lawyer? Used to be all you needed was the books and a good head. Before credentialism ate the field.)

The internet killed consensus reality. Now anyone can trivially disseminate arbitrary text. But the platforms on which those texts are seen are controlled by the new priests, line programmers, which determine how information flows. This is what critics of “the Facebook algorithm” et al are groping at. The many can create, but the few craft the landscape that hosts creation.

It’s still early. Remains to be seen if we can keep relatively open platforms (like Twitter circa 2010; open in the unimpeded sense). Or if the space narrows, new gatekeepers secure hold. But that will be determined by programmers. (Maybe lawmakers.) Rest along for the ride.

That’s all copy-pasted from Twitter and then lightly edited to be more readable in this format.

I included the opening quote about complex systems because although this neat narrative holds more truth than some others, it’s still a neat narrative. Don’t forget that. Reality is multi-textured.

Header photo by kev-shine.