There’s a Facebook page called Cyberpunk Is Now, followed by 696 people. The nameless creator narrates the ongoing digital revolution via links to Wired, Vice’s Motherboard, and similar websites, captioned with insightful or cutting comments.

I was curious about Cyberpunk Is Now’s motivation and background, so we did a Q&A. I edited their answers down to a newsletter-appropriate length, but the full transcript is available here. Full disclosure: I also made a few small grammar edits.

Blade Runner promo image.

Exolymph: What inspired you to start the Facebook page?

Cyberpunk Is Now: Well, I’ve always loved the notion that the world we’re living in today is the same dystopian world — not exactly, but eerily similar — that numerous cyberpunk authors warned us about. […] It went from merely observing the state of the world to actively working to inform people of it — and encouraging them to stay aware and fight back against corruption and tyranny in the coming post-industrial age.

Exolymph: What’s your personal political position? Do you consider yourself an anarchist, libertarian, or…?

Cyberpunk Is Now: It’s hard for me to define my political views through any exact term because nothing is ever absolute — what works for one country may be the bane of another, and I can only speak for the United States seeing as that is where I’m from. There are bits and pieces of many different political philosophies that I adore, but I prefer to stay away from labeling due to the various implications and misunderstandings that can arise.

In my opinion, the most desirable course of action in the present moment, given the present political and socioeconomic climate here in America, is to elect Bernie Sanders. I am only attempting to work from a short-term view here — I know that there are anarchists and anarcho-communists who’d rather just torch society altogether, and they aren’t wrong, but now just isn’t the time for that. Humanity has a bit of a way to go before we can start initiating huge shifts. […] At this point in human history, nothing too extreme is very feasible — we still have to work out way up to that. We have to be realistic about what we set out to do. We won’t be able to innovate if the top 1% of our society is holding nearly the entire sum of our wealth.

I know that scenario makes people want to throw bricks through windows and anarchy-it-up, but let me quote a favorite artist of mine, Pat The Bunny, to illustrate what I am trying to convey: “There’s no brick we can throw that will end poverty, and we can’t blow up SB1070. Things will never be as simple as when I was twelve years old reading Karl Marx in my bedroom alone.”

Exolymph: How do you think accelerating technology will affect people’s day-to-day jobs? What about the labor market overall?

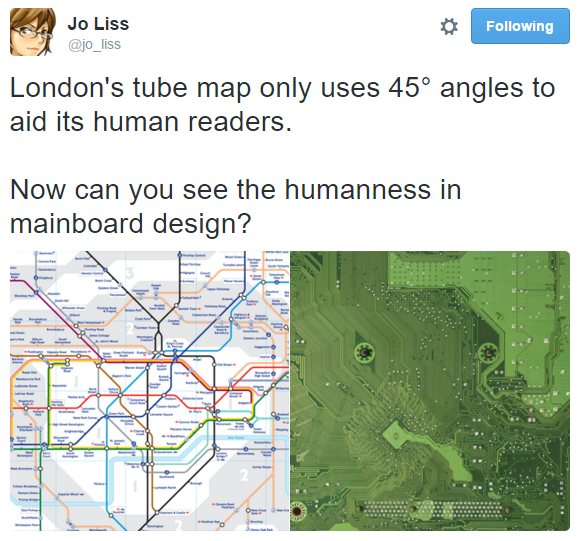

Cyberpunk Is Now: We’ve been seeing some version of Moore’s Law successfully play out since the turn of the millennium. Since technological advancement is exponential, not linear, it’s very hard to say where our society, or the world as a whole, will be at any amount of time in the future. Hell, I fully expect that even by 2017 I’ll be seeing things that I would have thought impossible today. People have been complaining about how “robots will take our jobs” (they just love to say that to demonize certain groups) like it’s a bad thing. But trying to hold that off would just cause us to stagnate.

Yes, many jobs will be replaced by automated processes and machines, but those machines themselves will create three jobs for every one job they take away! I always try to tell people that, if they fear such a scenario, they should go into the tech field in order to pursue the new positions this automation will create… however, these people would rather not educate themselves in any form or fashion, so my point is always lost to them. […]

Like I said, in the very near future, many jobs will be replaced with some form of automated technology, and this will open up three job opportunities for every one it closes, but the difference will be that there will, obviously, be certain requirements in order to fill these positions: technological prowess, intellect, problem-solving skills…

I know that my argument, “if you don’t want a robot to steal your job, get a job working on that robot” has an inherent flaw: automation will replace the jobs of people not qualified to work with technology. Hopefully this will finally push the ignorant masses to pursue education, at the very least in their own self-serving interest, in order to keep up. Politicians will certainly play on the fear and hatred of those who choose not to, just like a certain dickhead here in America is playing on people’s hatred of certain minority groups right now. Politics never changes. But, with the boundless sharing of information the internet has allowed, people are finally beginning to wake up and give a shit. […]

The way I see it, by the time all of this new tech rolls around, a certain type of ignorance will be banished forever from mainstream society. The people who complain that “immigrants are taking our jobs” will likely say the same thing in five years about robots. In ten years, this closed-minded attitude will leave them on the fringes of society. […] The triumph of knowledge, creativity, and innovation due to the increasing prevalence of (and dependence on) technology is all I’m sure about and can really say about the future. Truth be told, I’m excited.

Exolymph: What can you tell me about your real-world self? Day job? Hobbies?

Cyberpunk Is Now: I very much value individuality and self-expression in the ways I present myself, both through my appearance and the ways I go about communicating with others. I pretty much wear nothing but black and gray clothing (it makes doing the laundry easier) that I’ve found at thrift stores over the years. I don’t think I own a single garment that isn’t from some sort of secondhand store, actually. I also like to repair my clothing with dental floss and sometimes do some DIY stuff with patches or spikes to pass the time when I can’t sleep. I always have to carry around an inhaler and other medical supplies, so I prefer wearing leather jackets or hoodies with an abundance of pockets. […]

I never really learned how to make eye contact with others, so I’m always wearing a pair of sunglasses (classic mirror-shade aviators or black-lens teashades) and I’ve bullshitted my way into having everybody I know think I have a sensitivity to fluorescent lighting in order to justify the constancy of their presence on myself even when indoors.

People always say that “the eyes are the window to the soul”, and I like to think of my sunglasses as my own personal curtains.

So, pretty much, I’m the sort of person you’d expect somebody’s grandparents to gawk at if they saw them walking down the street. I actually love it. People always shit themselves when I’m polite to them, because they judge based on appearance and expect me to act like a dick. I almost get a high from proving people’s preconceived notions wrong like that. […]

Also… I smoke a lot of weed, and my favorite band is Nine Inch Nails, and — yes — those two facts are directly related. I read more often than I watch television, and try to relegate my video-game usage to the weekends because I sorta have an addictive, in some sense of the word, personality. I love existentialist literature, and due to the nature of this page you can probably guess what my favorite fiction genre is.

Cyberpunk Is Now exists on Facebook, which proves some kind of point about the future of media. Go follow the page.