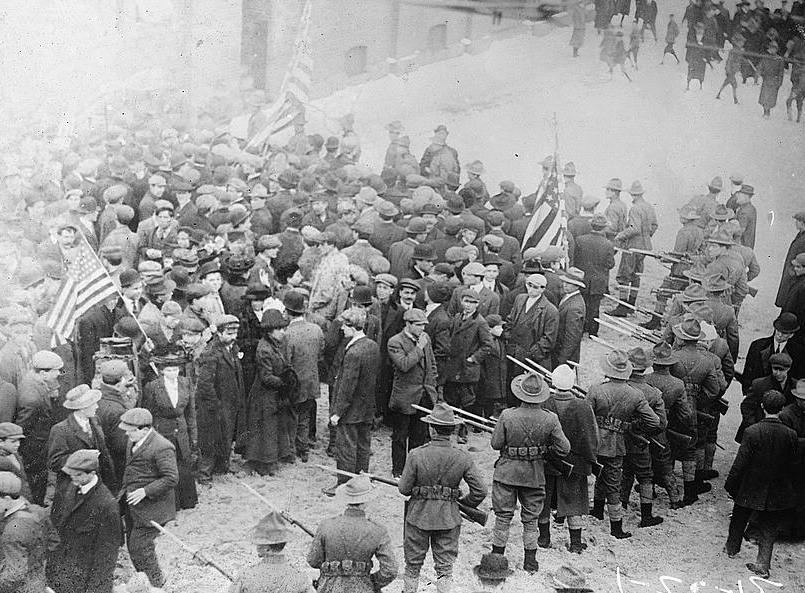

The “Bread and Roses” Lawrence textile strike of 1912. Photo via Library of Congress.

In recent musings about Las Vegas, I called myself bourgeois. Refresher: according to Karl Marx, the bourgeoisie are the capitalist class, prone to consumerism — also often associated with snobbery and intellectual affectations. Think New Yorker readers.

I bring this up because commenter gaikokumaniakku said, “There are a lot of folks who thought they were bourgeois, and then they woke up one morning to another rejected job prospect and realized that they were lower-class.” I agree with Scott Alexander that class does not solely hinge on money, but the point is a good one.

gaikokumaniakku also asked what I think of the term “precariat”, which is a play on “proletariat” (opposite of the bourgeoisie). The precariat are people without financial reserves or job security. Macmillan Dictionary’s BuzzWord blog published this in 2011:

“New, international labour markets, significantly expanding the available workforce, have weakened the position of workers and strengthened the position of employers. Increasingly, workers are in jobs which are part-time and/or temporary, have unpredictable hours, low wages and few benefits such as holiday or sick pay. This means that employers can follow what demand dictates and simply [fire people] if work is not available, and are also not obliged to pay anyone that isn’t actually working.”

I find it plausible that globalization is a big part of this. That’s been an ongoing trend: jobs once located in [country where labor is expensive] disappear offshore to [country where labor is cheap]. Workers don’t have the same freedom of movement that employers do, so they can’t easily respond to market changes. Larger companies especially, which rely on many people’s labor, can shift operations to wherever costs the least.

Demonstrators in New York City during the 1913 May Day parade. Signs feature Yiddish, Italian, and English. Photo via Library of Congress.

Priest and professor Giles Fraser wrote a Guardian editorial on this very topic:

“In this era of advanced globalisation, we believe in free trade, in the free movement of goods, but not in the free movement of labour. We think it outrageous that the Chinese block Google, believing it to be everyone’s right to roam free digitally. We celebrate organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières for their compassionate universalism. But for all this talk of freedom from restriction, we still pen poor people into reservations of poverty. […] At present, globalisation is a luxury of the rich, for those of us who can swan about the globe with the flick of a boarding pass. The so-called ‘migrant crisis’ is globalisation for the poor.”

The other macro factor that might be creating (and provoking) the precariat is technological unemployment. The machines are taking our jobs!!!!! Ahhhhh!!!!! My guess is that we’ll adjust to new levels of productivity, like we did after the Industrial Revolution, but the transition phase will be very painful. (I basically stole this theory from Ben Thompson.)

Beyond that, I don’t have any particular insights. If you do, hit reply and let me know?

gaikokumaniakku says:

An interesting fact is that William Gibson was poor by choice before he wrote Neuromancer.

He was garbage-picking and selling mechanical junk for cash.

That definitely gave him an insight to the “punk” side.

Now, more than thirty years after Gibson’s voluntary refusal to work a steady job, we have a lot more humans, most of whom want to work a steady job but can’t. It’s a little bit different from Gibson’s flirtation with poverty.

Sterling talks about “favela chic.” He has little idea what it’s going to look like, and he refuses to talk about the practical development of it, e.g. in Venezuela. He hosts talks where he raises the topic and then refuses to talk about it because it depresses him.

June 17, 2016 — 3:46 pm

gaikokumaniakku says:

A relevant story is :

The Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro has declared a financial emergency less than 50 days before the Olympics.

Interim Governor Francisco Dornelles says the “serious economic crisis” threatens to stop the state from honouring commitments for the games.

Most public funding for the Olympics has come from Rio’s city government, but the state is responsible for areas such as transport and policing.

Interim President Michel Temer has promised significant financial help.

Rio state employees are owed wages in arrears. Hospitals and police stations have been severely affected.

The governor has blamed the crisis on a tax shortfall, especially from the oil industry.

In a decree, Mr Dornelles said the state faced “public calamity” that could lead to a “total collapse” in public services, such as security, health and education.

He authorised “exceptional measures” to be taken ahead of the Games that could impact “all essential public services”.

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-36565901

As Gibson is often quoted as having said: “The future is here already, it just isn’t evenly distributed yet.”

If the financial crisis from Brazil gets distributed to a few more countries, war might not be enough to reboot the global economy. That won’t stop the war-pigs from selling war…

June 17, 2016 — 4:09 pm

Sonya Mann says:

1) fuck the Olympics

2) http://gunshowcomic.com/648

June 18, 2016 — 1:27 pm

gaikokumaniakku says:

http://gunshowcomic.com/899

June 18, 2016 — 3:40 pm